AUGUSTINE’S GNOSTICISM AND OTHER WRONG ACCUSATIONS (2)

On Original Sin, Free will and Unilateral Determinism

In my previous article, I tried to dispel the supposed shadow surrounding the influence of St. Augustine’s past on his theology. Hopefully, you would agree with me that neither Manichaeism nor Neoplatonism so held the Bishop of Hippo as to taint his theology.

Without much ado, I would go on to dispel various myths about Augustine’s theology, beginning of course with Original Sin. Although this is only a broad overview, it should serve our cause.

Augustine, The Innovator

Even though the genius of St. Augustine made him well-fitted to systematize many doctrines more thoroughly than his predecessors, Augustine was by no means an innovator. Instead, he saw in his works a calling to preserve the universal and apostolic faith.

I have not quoted these words as if we might rely upon the opinions of every disputant as on canonical authority; but I have done it, that it may be seen how, from the beginning down to the present age, which has given birth to this novel opinion, the doctrine of original sin has been guarded with the utmost constancy as a part of the Church’s faith, so that it is usually adduced as most certain ground whereon to refute other opinions when false, instead of being itself exposed to refutation by any one as false. Moreover, in the sacred books of the canon, the authority of this doctrine is vigorously asserted in the clearest and fullest way.1

Ironically, Augustine could identify that it was the Pelagians who were presenting novel opinions to the church. It was in the bid to defend the traditional faith that he once again earned the tag Manichaean.

While it may be right to credit St. Augustine (354-430AD) with the first use of the term “Original Sin” and with a fuller exposition of the concept, it would be inappropriate to assert this concept was entirely missing in the Ante-Nicene church.

Excellent scholars like Marta Przyszychowska have shown us that while the term “Original Sin” was not employed, the church of the first three centuries had a concept of hereditary corruption (corruzione ereditaria). It is this corruption that causes humanity to multiply its sins and submits it to eternal death. This corruption is transmitted because there is a real or mystical unity of mankind to its first ancestor.

Though the Fathers had different ways of cashing out the concept, there was a great level of convergence across the centuries. Even across geography, as Marta traces out, the Greek fathers (who were somewhat independent of the influence of the Latin church) show this convergence as well. She notes that whether Greek or Latin, the Fathers speak in one voice; and Augustine only sings in this choir of the Fathers.2

Iranaeus (c. 130-202AD)

For we were imprisoned by sin, being born in sinfulness and living under death.3

He clearly shows forth God Himself, whom indeed we had offended in the first Adam, when he did not perform His commandment. In the second Adam, however, we are reconciled, being made obedient even unto death. For we were debtors to none other but to Him whose commandment we had transgressed at the beginning.4

Tertullian (c. 160-220AD)

Every soul, then, by reason of its birth, has its nature in Adam until it is born again in Christ; moreover, it is unclean all the while that it remains without this regeneration; and because unclean, it is actively sinful, and suffuses even the flesh (by reason of their conjunction) with its own shame.5

Methodus of Olympus (c. 260-331 AD)

When the Apostle says, for I know that in me—that is, in my flesh—dwelleth no good thing, by which words he means to indicate that sin dwells in us, from the [first] transgression, through lust, out of which, like young shoots, the imaginations of pleasure rise around us6

Origen of Alexandria (c. 185-254AD)

If then Levi, who is born in the fourth generation after Abraham, is declared as having been in the loins of Abraham, how much more were all men, those who are born and have been born in this world, in Adam’s loins when he was still in paradise. And all men who were with him, or rather in him, were expelled from paradise when he was himself driven out from there; and through him the death which had come to him from the transgression consequently passed through to them as well, who were dwelling in his loins.7

Gregory of Nyssa (335-395 AD)

At the outset it is from passion we get our origin, with passion our growth proceeds, and into passion our life declines; evil is mixed up with our nature through those who from the first allowed passion in, those who by disobedience gave house-room to the disease. Just as with each kind of animal the species continues along with the succession of the new generation, so that what is born is, following a natural design, the same as those from which it is born, so from man is generated, from passionate, from the sinful its like. Thus in a sense sin arises together with those who come into existence, brought to birth with them, growing with them, and at life’s end ceasing with them.8

Cyril of Alexandria (c. 376-444 AD)

For our nature contracted the disease of sin because of the disobedience of one man, that is Adam, and thus many became sinners. This was not because they sinned along with Adam, because they did not then exist, but because they had the same nature as Adam, which fell under the law of sin. Thus, just as human nature acquired the weakness of corruption in Adam because of disobedience, and evil desires invaded it, so the same nature was later set free by Christ, who was obedient to God the Father and did not commit sin.9

It is manifestly clear that Augustine did not suddenly sow seeds of gnostic heresies to a sheepish church with its spell-bound theologians. That is a rather low view of a church that had hitherto gone through the fires of persecution and intense battles against manifold heresies.

Any modern preacher who wishes to deny the doctrine of Original Sin must see that he stands not against the lone voice of St. Augustine, but against the host of the early and most reliable witnesses.

More Innovations?

It is also asserted, albeit wrongly, that Augustine alongside inventing the doctrine of original sin, also invented infant baptism.

It is first good to note that the Pelagians, Augustine’s opponents also practiced infant baptism. Indeed, way before Augustine, there was a general admission of infant baptism and it was already well on its way to universal practice.

Many currents lead to the widespread adoption of infant baptism in the ante-Nicene and Nicene church, most important of which was the conviction that it was of apostolic origin. Origen comments:

“The Church received from the apostles the tradition of giving baptism even to infants. For the apostles, to whom were committed the secrets of divine mysteries, knew that there is in everyone the innate stains of sin, which are washed away through water and the Spirit”10

Cyprian, and a council of sixty-six bishops held at Carthage in 253AD affirmed the practice of infant baptism.11

On Free Will and Unilateral Determinism

It is asserted that Augustine in affirming Original Sin against the Pelagians, denied free will. But here is Augustine affirming free will even in his polemics against Julian, a Pelagian:

He further asserts about the wicked who sin:

Augustine in fact wrote one of the best treatise on free will in his time titled On Free Choice of the Will (De Libero Arbitrio, 388-395 AD). His view on free will indeed evolved; but this evolution was towards a coherent and integrated system with his other doctrines, without ever denying free will. Augustine in his later writings began to emphasize the primacy of grace in salvation, with free will playing a secondary role. In his fully fleshed out view, God’s grace is the sole cause of salvation, and human will merely responds.12

Ironically, Augustine accuses the Pelagian system of actually destroying free will since it exalts its powers above the much needed grace of God.

He maintains with the host of witnesses that our free will requires purification from the effects of sin for a proper response to grace.

Augustine maintained that the first good inclination of the will is a gift of God. God through a specially efficacious providence has prepared the good movement of the will.13

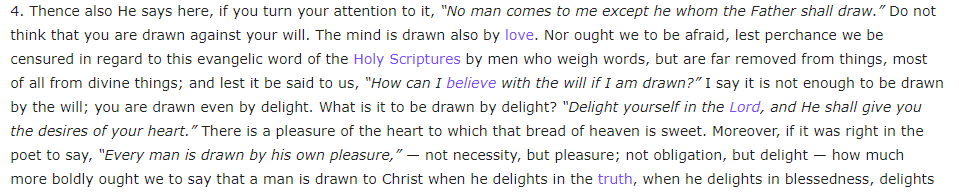

Nowhere does he describe God’s drawing grace (his gratuitous predestination) as a tyrannical impulse imposed by the stronger on the weaker. He rather describes it as an attraction which is without violence to the will. It is an appeal, a luscious attraction, a supreme delight that seeks to persuade. In his treatises on the gospel of John he shows the impossibility of believing unwillingly; rather, grace makes us willing.

Having set up a paradox between being drawn and believing willingly, he goes on to explain the tension:

We are drawn by delight!

Can We Say the Grace?

We have so far seen that Augustine has maintained that he had definitely shaken off his Manichean influence; defers to the authority of scripture above Plato; and defends the faith of the fathers against innovators. We have also seen that Augustine maintains the primacy of grace without demolishing free will; rather, he establishes it.

But what about the alleged misinterpretation of Romans 5:12 and Augustine’s limited knowledge of the Greek language? What about his hypnotic effect on all theologians and Councils by which his views were gobbled up wholesale for thousands of years? We consider these in the last installment of this essay and offer valuable lessons from the life of Augustine.

For now, how best might we sum up the system of the blessed Doctor of Grace? No better way than with his own words:

For it is only of unmerited mercy that any is redeemed, and only in well-merited judgment that any is condemned.14

Przyszychowska, M. (2018). We Were All in Adam: The Unity of Mankind in Adam in the Teaching of the Church Fathers. Warsaw, Poland: De Gruyter Open Poland. 2.2 https://doi.org/10.2478/9783110620580.

Irenaeus, Demonstration of the Apostolic Preaching 37; SCh 406, 134; transl. J. Armitage Robinson, 103.

Irenaeus, Against Heresies V 16, 3; SCh 153, 220; transl. ANF 1, 544

Tertullian, De anima 40; PL 2, 719, CSEL 20, 367; transl. ANF 3, 220.

Methodius of Olympus, De resurrectione II 6, 4; GCS 27, 340; transl. ANF 6, 372.

Origen, Commentary on the Epistle to the Romans V 1, 12; SCh 539, 364-366; transl.

Th.P. Scheck, vol. 1, 311

Gregory of Nyssa, Orationes VIII de beatitudinibus, hom. VI; GNO 7/2, 145; transl. S.G. Hall, 71.

Cyril, Romans, Ancient Christian Commentary on Scripture, New Testament, Gerald Bray, ed. [Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 2005], 142-43

Origen’s Commentaries on Romans 5:9 [Post A.D. 244].

Schaff, P. (2014). History of the Christian church (Vol. 2, Ante-Nicene Christianity). Hendrickson Publishers, V.73.

Retractions (Book II, Chapter 42).

Retractions, I, ix, n. 6.

Handbook (Enchiridion) of faith, hope and love, Chapter 94

Autocorrect messed everything up.

No he wasn't accused of hypnotism qua hypnotism. It is just my figurative way of presenting what his critics assert...

No, he wasn't accident of usung hypnotism qua hypnotism. It is just my digital way of present what his critics assert; that every one after Augustine simply swallowed his views, hook, line and sinker.