I feel a certain indebtedness to offer a review of this work firstly in service of the truth, and secondly because it was a stream from which I once drank and many of my friends still do. My former subscription to it was in part due to a yearning for a cure to the epileptic state of theology in the Nigerian Church (frankly obvious for all to see), which Pastor Onayinka was making efforts to address. I have since learnt that the best method to address this corruption is not by innovations or novel propositions but by recovering orthodoxy. After all, it was Pastor Onayinka who said:

“While Science and Commerce thrives on innovations, Christianity thrives on its traditions”

By reviewing “God Who Became Jesus”, I point out his inconsistency with this principle, not for destructive ends, but for reformative ends so that that stream from Oweh can be, if ever possible, truly beneficial to drink from.

I must first commend the grit and rigor required to gather data to assemble over a thousand pages of what one believes to be the truth. Sadly, having a data-cramped and sophisticated exegesis does not equate to sound exegesis, in so far as the data is not processed into correct information. It is impossible to highlight all the points where the author falls short, hence I focus on a few major points.

Short of Scholarly Standard

I would hardly expect a book so hurriedly pushed to the printing press that the editor’s notes weren’t properly implemented to meet scholarly standards.

I kid you not, this is live from the book.1

That aside though, the book is an improvement compared to other publications by the author as he makes more effort to include references. Yet, it still falls short of scholarly standards. These issues have been flagged elsewhere, hence I won’t repeat myself.

It doesn’t take too much to see that many of the ideas in the book find their source in Dr. Michael Heiser, but he is never cited. Aside from the many under-referenced and uncorroborated claims, the references cited are cited in a manner that does not escape the charge of plagiarism, as several pages from other people’s works are duplicated verbatim into this book.

It is recommended by most publishing guidelines that one quotes no more than four to five lines of another author’s work at a go. But this rule was repeatedly flouted by this author in referencing NT Wright’s book, random blog sites, and online encyclopedia. A reference from Jehovah’s Witnesses’ Watchtower Mission was a whopping eight pages long duplicate.2

Another marker of a good scholarship is a good literature review. Anyone who has done research work in undergraduate or postgraduate studies knows that one must do a thorough literature review and justify one’s unique contribution to the body of knowledge. Thus, for a Christological work such as this, we should expect to see interaction with the landmark Christological works of the past.

This author however kept on casting the historic theologians of the church as being puzzled by the topic while, in fact, much of the universal church’s Christological affirmations had been settled at the Council of Chalcedon as early as 451 AD. Even during the reformation (16th Century), matters of the Trinity and Christology were not disputed points between the Catholic Church and the reformers.

Those who have been branded heretics in the church are those who saw the need to deviate in substance from or completely jettison this creed.

Author’s Position on the Trinity?

One point I found interesting about this book is that save for mentions of the Trinity by the sources referenced in this book, this author never directly references the Trinity. It is widely known that Christology rises and falls with the Doctrine of God i.e. the conception (or not) of the Trinity.

I was eager to know whether this author agreed (or not) with the orthodox formulations of the Trinity encoded in the Creeds (Nicene and Athanasian) but he never really makes this clear. When he references the Nicene creed, he issues several caveats such as “Creeds are useful but must be cautiously handled”, “However, if such caution is not observed, creed would be considered as the interpretation of scriptures”, “The creeds are not meant to be an end. Rather, they should prompt a constant rethink, a rework of the implication of what it means to have a Jesus-centered faith”.3

In the author’s bid to rethink and rework things, he labors to come to a strange conclusion about the distinction between the Father and the Son.

These are two different sections of the book, so we can be sure it was not a slip of tongue. As an aside, it is a regular feature of this book to go over something that has been previously covered almost verbatim, making for a tedious read.

Back to the point though, the author asserts that the one Yahweh is distinguished to two personalities by visibility—one visible and one invisible. Now, if by this he refers to the visibility of Yahweh as Christophanies (God the Son made tangible to human senses), that could have been excused since there is wiggle-room for that in orthodoxy. But the author is referring to the fundamental nature of the Son as visible. That is, the Son ad intra (or in his immanence) is visible as opposed to the invisible Father.

One problem with this is that visibility requires circumscribability. For to be seen is to be defined, to be bounded, to be limited in some way. This implies spatiality and finitude. To predicate visibility as the distinctions of the Two Yahwehs (as he often says) is to identify two essences, with the son as an inferior essence. Thus, when orthodox theologians speak of the pre-incarnate visibility of the Son, they speak of it as the Logos Prophorikos (sent forth), a gracious manifestation by way of divine condescension to the human senses. This is conceptually distinguished from the Logos Endiathetos (Immanent), which is the Logos in himself before the world began, before there was any human eye or sense to see him.4 He is in that way (that is, in his essence) as invisible as the Father is.

Hence, since this author’s attempt to distinguish the Father and the Son by way of visibility fails (as it leads to bitheism), there remains for him a want of distinction between the Father and the Son. Perhaps this author should have leaned more on the orthodox trinitarian formulations rather than rely too heavily (even though they are helpful) on the Binitarianism of certain second-temple Jewish texts.

The author’s modus of distinction of the Spirit from the Son is even more questionable and reeks of modalism. Though he rightly identifies the Spirit as God, he defines the Spirit as “Jesus dwelling in the believers”.

As time and space will fail me to unpack this, I can only appeal to my readers to consult orthodox theologians for the correct understanding of the distinctions of the persons of the Godhead.

Jesus, The Actor

Perhaps the most perplexing find—I reserve the most disappointing find for part 2—in this book is the assertion that the Old Testament Prophets did not prophesy about distant future events and did not have Jesus in mind in their prophecies.

The Old Testament prophecies were not really about Jesus, rather they were pre-written scripts that Jesus was adept at acting out. Jim Caviezel has got nothing on him. Worse still, it could simply have been the disciples artificially organizing the story (since Jesus himself did not write the gospels) to fit the previous patterns found in the Old Testament.

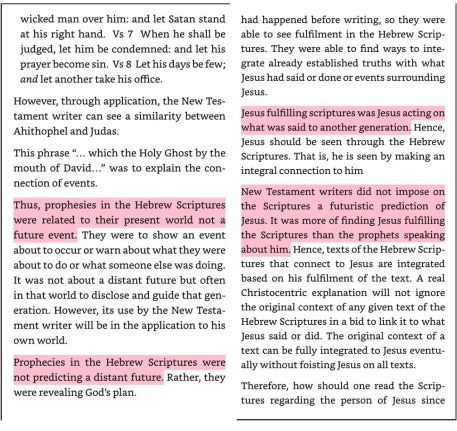

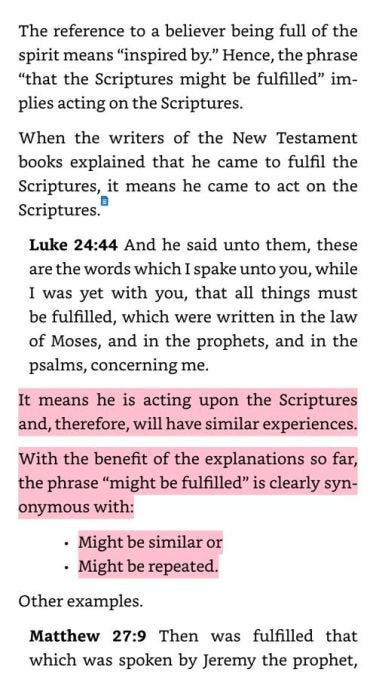

To accommodate this thesis, the author goes on to give a watered-down definition of the word “fulfillment”

Fulfillment was Jesus being full of the spirit and inspired to act similar to previous patterns! “Might be fulfilled” means “might be similar” or “might be repeated”. This is beyond bad, this is—and I am seriously restraining myself here—ridiculous.

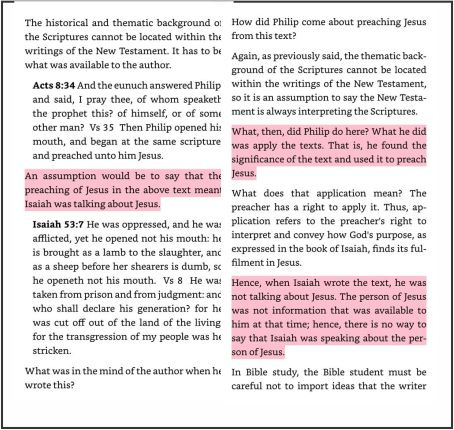

The author provides an example:

Isaiah wasn’t speaking about Jesus! It is interesting that the author contradicts an earlier work of his, published in 2019.

I am unaware that there has been any public admittance that these previous conclusions were erroneous, and neither has this book been withdrawn from circulation. What gives in the face of glaring contradictions not only with the former works, but most importantly with scripture?

10 Concerning this salvation, the prophets who prophesied about the grace that was to be yours searched and inquired carefully, 11 inquiring what person or time[a] the Spirit of Christ in them was indicating when he predicted the sufferings of Christ and the subsequent glories. 12 It was revealed to them that they were serving not themselves but you, in the things that have now been announced to you through those who preached the good news to you by the Holy Spirit sent from heaven, things into which angels long to look.5

45 Philip found Nathanael and said to him, “We have found him of whom Moses in the Law and also the prophets wrote, Jesus of Nazareth, the son of Joseph.”6

15 “Fear not, daughter of Zion; behold, your king is coming, sitting on a donkey's colt!”

16 His disciples did not understand these things at first, but when Jesus was glorified, then they remembered that these things had been written about him and had been done to him.

41 Isaiah said these things because he saw his glory and spoke of him.7

Should we believe the witness of scripture or half-baked novel ideas?

OT text must be interpreted as having reader relevance to its immediate audience, but this does not take away their double entendre. Several scholars like Richard Bauckham have noted that OT prophecies “combines a contextual specificity of relevance to its first readers with a kind of eschatological hyperbole that intrinsically transcends their context.”8

That intrinsicality is essential for defending the legitamacy of Jesus as Messiah. The artificial pattern repetition proposed by this author is not only ineffective, it also poses a danger to Christian theology.

Let’s keep Christianity preserved by its tradition.

Till part 2!

Referenced paginations are as published on Amazon.com

Chapter 4, Part A: Views about Jesus (Jehovah’s Witnesses Views) pp777-784

Chapter 4, Part C: The Creeds, pp 154-155

See entry of Logos in Muller, Richard A. Dictionary of Latin and Greek Theological Terms: Drawn Principally from Protestant Scholastic Theology. Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Book House, 1985.

1 Peter 1

John 1

John 12

Bauckham, Richard. The Theology of the Book of Revelation. Cambridge University Press, 1993. p155

To be honest, I felt compelled to agree with some of the things the author espoused in the book. I found myself saying, “Hmmn, this makes some sense... What if this is true?”

But the fact that those ideas are mostly novel, not supported by church history, and demand loyalty to a framework for intepreting the scriptures means I'll never interpret a simple text as it is. I'd have to contort and bend and reshape to remain true to that framework. It's just. . .dangerous.

Besides having to uphold tradition, things like this force one to put on that critical thinking hat.

This has been an insightful review; I look forward to the second.

Kai. This can be likened to defamation of character and personality of Jesus. Literally positing that he "role-played" old testamental writings is nothing short of conjectures that aren't biblical. This author's explanation must not leave out the other scenarios that are related but not directly acted out by Jesus himself, which fulfilled old testament scriptures e.g people of Jerusalem hailing Jesus as king on his triumphant entry, the preparation and acquisition of the upper room for the last supper, the under-two children killed by Herod and the horrendous lamentation that followed the massacre. All of these "incidents" are too precise for an ineptitude (though novel) ideology to dissuade men from accepting their divine foretelling. I wouldn't want to believe the author is naive since he once expounded the truth in the past. Perhaps, this kind of error wouldn't surface if one will stay sincere with the tradition of faith and the truth with pure conscience, and constantly resisting the temptation to be "innovative". I'm not surprised as this kind of heresy is in itself a fulfilment (acting out, pardon me 😀) of prophecy (1 Timothy 4:1&2, 2 Timothy 3:1&2)